Say the name Dr. Ming Wang, and lots of folks scoff. Why is an eye surgeon doing ballroom dancing in those commercials, the ones that air over and over and over again?

It all kinda feels showy, right? Ballroom dancers never perform eye surgeries in their commercials.

Wang says he's just looking for a way to stand out in a competitive Lasik eye surgery market.

But that's not why he started ballroom dancing. Wang says he learned to dance to save his life.

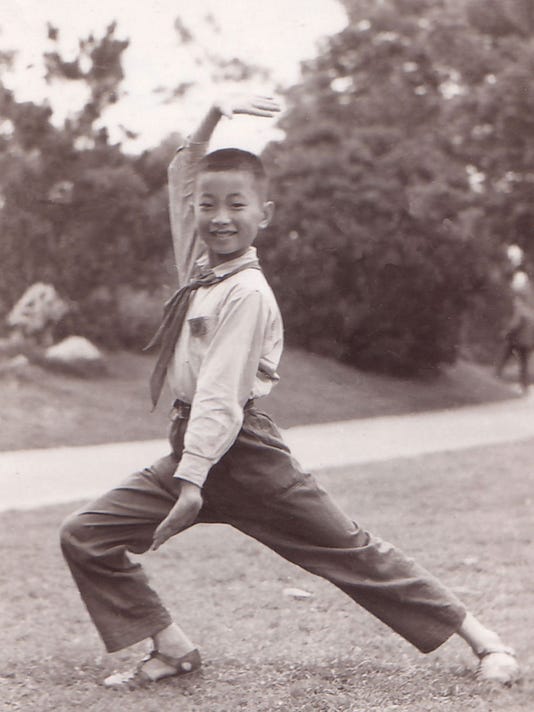

Wang, grew up in China when most youths from his city were banned from school and deported to rural farms to do hard labor. The labor proved to be too much for some kids, and many died.

But there was a way out: Children and teens who could dance, sing or play instruments well.

So a young Wang learned to play the ancient Chinese violin, the erhu, and he later learned to dance.

"The reason for my learning music and dance was not for love of music but for the sheer need to survive," he said.

Making something out of nothing

Wang grew up the oldest son of a couple of physicians in Hangzhou, a city of 2.5 million in eastern China.

Still, the family was poor: Mom and Dad, combined, made only the equivalent of $15 a month. They all shared a one-room apartment in a crowded building, where 12 families shared one bathroom.

The coal-fueled stove was out in the hallway, also shared by other families on the floor.

Ming Wang, at 16, is top and center in this family photo. Left to right are his mother, Alian; his younger brother, Ming-yu; and his father, Zhensheng.

Growing up in a crowded apartment in a crowded city, Wang still found himself lonely as a boy. He often was left with neighbor families who had lots of their own kids. And those neighbors usually put him in a high chair alone in a corner for most of the day.

Eventually, the boy learned to entertain himself by making his own toys out of cardboard and fabric scraps he found in street dumpsters. He got good at sewing and gluing and creating. When Wang was 8, his brother, Ming-yu, was born, and the older brother made toys for him as well.

Ming Wang started putting on puppet shows for his brother and neighborhood kids.

"I'm not surprised he became a surgeon. He always had nimble hands," Ming-yu Wang said in a phone interview from his home in Chicago.

"He made clothes for different roles. He put on original plays. And he put on these old Chinese operas by himself."

Of all the characters Wang created, his favorite was the Monkey King, who went on adventures to seek out Buddhist teachers for guidance.

The Monkey King was tenacious, single-minded and creative, all the things the young Wang wanted to be.

"So I was the Monkey King in my mind," he said, smiling slowly.

Ming Wang, 15, practices the erhu, an ancient Chinese violin.

Wang's mother, Alian, and father, Zhensheng, always stressed education, telling their sons that math, physics and chemistry will take them anywhere they want to go in life.

But his father had a hobby: ballroom dancing. And that fascinated his oldest son, who would stare at his dad when he danced at hospital functions.

"He was very handsome. He was the tallest one there," Wang said.

Wang was mesmerized by the music, the beauty of the dance — and the attention his father received when he performed.

"I always wanted to have some attention," he said. "Ever since I was 1, the only way for me to get attention was to be creative and to make something out of nothing."

'You get in or you get deported'

During his childhood, he saw older teen boys deported to lives of hard labor in rural areas. If those boys tried to come back to the city, they were killed, he said.

"I was distraught. It was particularly hard because I was a good student. I was in the wrong country at the wrong time."

So Wang — with his parents' help — tried to get into the performance band.

First, he started taking private Chinese violin lessons from a man who taught them in exchange for free health care from Wang's parents.

Wang eventually made it to music school, but that school suddenly was shut down.

So that's when he started to learn how to dance, first from his father, then private lessons, given, again, in exchange for free health care from his parents.

"I was very nervous. I was practicing all the time. Either you get in or you get deported," he said.

Wang had no recorded music, so he would accompany himself by singing songs, leaving him breathless as he danced.

Wang got pretty good, but the government stopped recruiting new members for the band, leaving Wang hopeless, scared, destined to go to the rural labor camps.

Turns out Wang staved off deportation for just long enough: In 1976, schools were reopened to teens in China after that.

Fearful that the government would restart deportation, Wang, through intense studying, said he jumped three grades to get into the high school graduating class.

In just three months, Wang took the college entrance exam and passed, opening the door for him to attend University of Science and Technology of China, the MIT of the Far East.

From there, Wang met a professor visiting from America, and, with $50, he moved to the States and launched the career that would launch all those ballroom-dancing commercials.

Wang is grateful for the opportunities: He gives back by spending thousands of hours and dollars doing surgeries that help restore sight for blind children overseas.

'He likes attention'

His younger brother greatly admires what Wang has accomplished, and he's grateful that Wang eventually moved him and his parents to America.

Ming-yu Wang concedes that Ming Wang is a bit of an attention seeker.

Ming Wang dances a tango in a 2007 competition. Wang first learned to dance from his father, a physician, and then he took private lessons

"The older brother, he played the role of the parents, they tend to be more aggressive and dominant," Ming-yu Wang said. "He likes attention."

Ming Wang has a slightly different explanation of those ballroom-dancing commercials.

"In my ads, I combine medicine with art," he said. "It is more fun, and it works better. You remember it!"

Reach Brad Schmitt at 615-613-4815 or on Twitter @bradschmitt.

Click here to read the article on Tennessean.com.