The Right Place . . . The Right Time

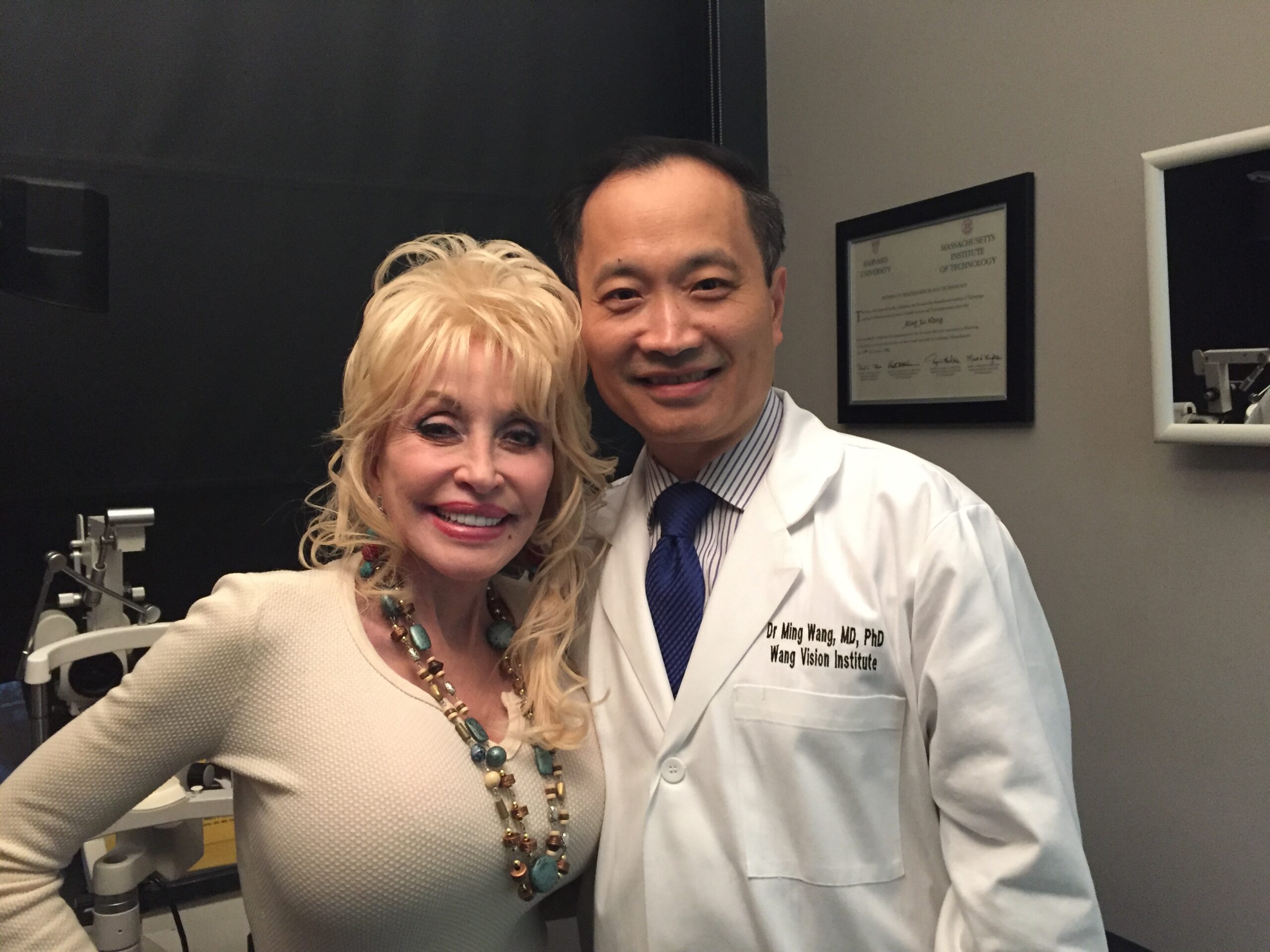

Celebrity patient Dolly Parton with Dr. Ming Wang

Celebrity patient Dolly Parton with Dr. Ming Wang

Who is Dr. Ming Wang? That is probably your precise question at this very moment! Krista Martinelli, administrator, founder, and editor for AroundWellington.com was my “date” for the night. It was a fateful Saturday night, and I was honored to have been invited to see the annual Royal Palm DanceSport Championships NQE and WDSF Open Palm Chapter #6016 which was organized by Krista’s father, Dave Koontz and her Stepmom (also president of the Board), Connie Barnhart. When we looked at our tickets and found our table, we saw a distinguished-looking man and his family sitting in what we though were “our seats”. And, we told him, very boldly, “we think you might be at the wrong table”. The man smiled at us, moved over gently, and we felt ridiculous as we had just put our “foot in our mouths”. This “stranger”, unbeknownst to us, was one of the dancers. He had a number tag on his back and was sitting with members of his family. After this awkward and “accidental” encounter, the situation improved. Krista and I discovered that this man was not just a brilliant ballroom dancer and an interesting conversationalist, but also a prominent laser eye surgeon.

After meeting Dr. Wang, Krista and I gave each other that knowing look and I spoke up proudly…well…maybe more of a whisper. I said, “HE is my next interview”.

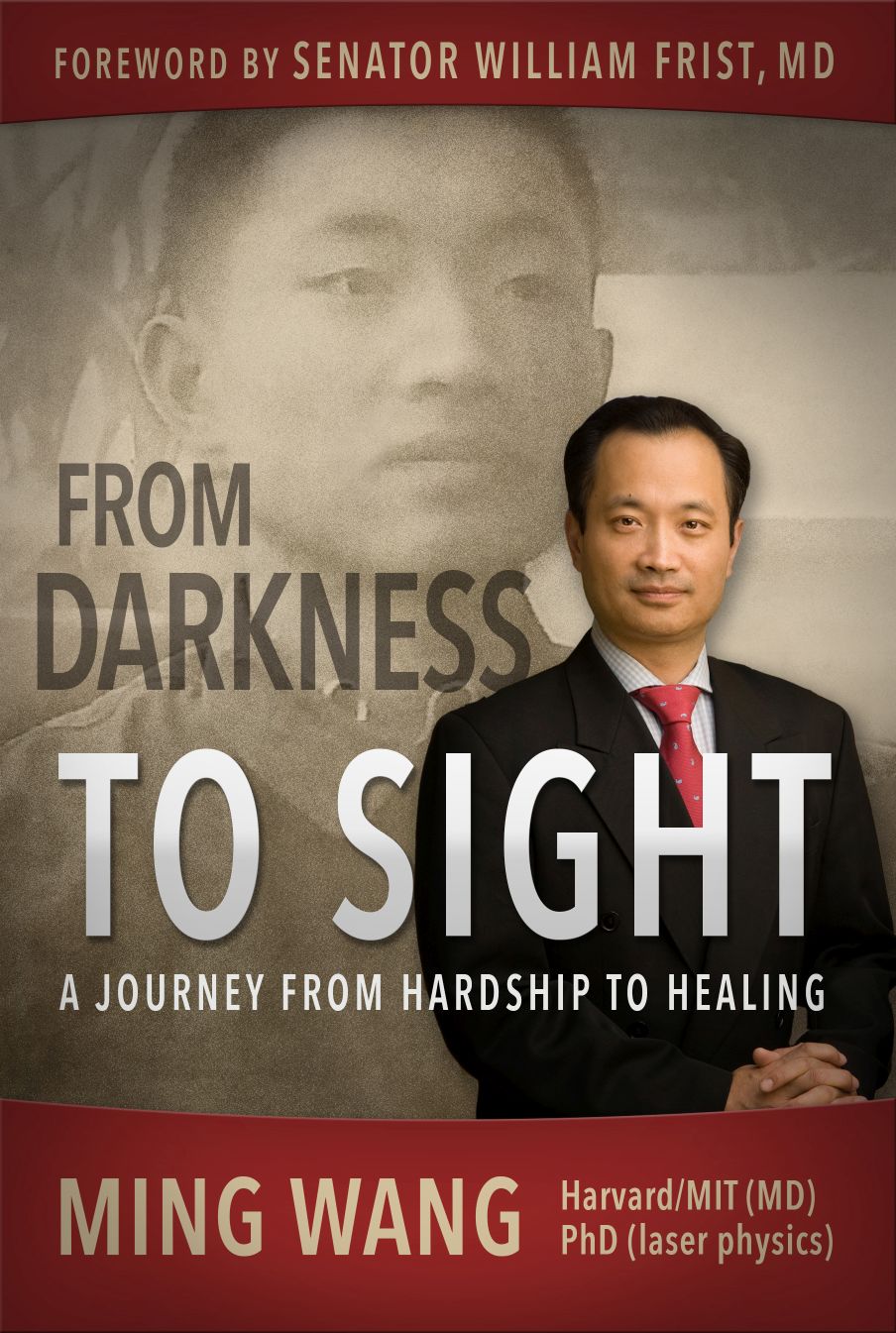

Dr. Ming Wang is an exemplary eye surgeon and philanthropist. He is also the author of the book, From Darkness to Sight. The book is a very moving biography encapsulating how one man’s journey of fear, poverty, and prejudice was transformed into a mission to create love and perform miracles. He is a shining example of perseverance and dedication.

Dr. Ming Wang

Dr. Ming Wang

“Reach out and touch someone…”

Our interview began over a phone call. It was probably one of the most significant and emotional calls that I have ever participated in with an individual. Although the interview was a little over two hours, the knowledge and insight I gained is timeless and will forever be a turning point in my life. Please keep in mind the following:

- You will be reading for a LONG TIME. There is no way to make the complexity or magnitude of this article brief.

- The interview may feel “uncomfortable” at times, but it is an amazing learning experience for all to read.

- After the article, you WILL “know” Dr. Ming Wang.

Dr. Wang lives in Tennessee, so I was mindful of the one-hour time difference from the start. He was extremely gracious at the very beginning, thanking me for this opportunity. Let’s get straight into the interview.

AW: Reading your book was extremely emotional for me. I learned a lot about China during that period. Was it difficult for you to revisit your past to write this book?

DMW: Yes, many of the memories have been suppressed over the decades because they are painful. But I had a need to write to recall those times, even the tough experiences. I had to relive these tough events to write the book. However, looking back, I gained a new perspective when I wrote the book on past event events and it enabled me to put my efforts into humanitarian causes. (We just touched on these briefly, because they are discussed more in detail later in the interview). I have two foundations that I began in conjunction with medicine that helped me to “give back” to the community. One is the Wang Foundation for sight restoration that helps blind, orphaned children obtain eye surgeries and eye treatment free-of-charge; and the other is a non-profit organization called The Common Ground Network. I think that because I suffered physically and emotionally in a society with extreme polarization (in China during 1966 to 1976), I want to help people find common ground, resolve gridlock, and find solutions to problems in our society.

When I came to this country, I fell in love with America because of freedom and mutual respect. One quote that I heard in this country that has stayed in mind is, “I may not agree with what you say, but I will defend your right to say it”. So, America was a breath of fresh air for me and a newfound freedom and I have enjoyed and appreciated living here. However, in recent years America has actually departed from freedom and mutual respect. Our nation is polarized. We are increasingly fixated on how we are different, rather than appreciating what we all have in common. I want to help others because I have suffered and also help others who are dealing with racial tension through teaching methodologies to help depolarize, to bring everyone together. Polarization stagnates our society; it is the depolarization and bringing people together to find the common ground that moves our society forward, to bring our country back on track.

Three musketeers (Jason, Wang and Ji-hong) arrived in America, nearly penniless but formally dressed in 1982

Three musketeers (Jason, Wang and Ji-hong) arrived in America, nearly penniless but formally dressed in 1982

AW: You are a prestigious Harvard graduate, laser eye surgeon, ballroom dancer, and musician. You wear so many “hats”. Tell us how you manage it all. How has music and dance affected your life?

DMW: I am able to manage different interests because I find that as a whole, we make time to do things that we truly love and are passionate about. As humans, we complain that we “don’t have time,” but that is not the source of the problem. The question is really: Do we really want to do it? If we WANT to do it, we make an effort, we make it happen no matter the struggle or sacrifice. I want to be involved in many of these meaningful things. Music and dance have affected my life tremendously, especially in practicing medicine. Let me explain further (he says with a quiet pause and with the same tone he would use to reminisce about a loved one).

Medicine, despite all of its great technological advancements is missing two crucial elements today: the personal touch of a doctor, and the emotional connection between a doctor and his/her patient. Technology in many ways has actually increased the distance between the doctor and the patient. Doctors send out tests, but don’t listen to or talk to the patient and try to understand about their feelings. At the end of the day, it is not what we as doctors think that is important, it is what the patient feels important. Medicine SHOULD be about the following: listening, talking to patients, and feeling what our patients are feeling – that is the bottom line and that is how I go about practicing medicine.

I interrupted the interview briefly because Dr. Wang struck a sensitive nerve. As a cancer survivor, I had the aforementioned problems with dealing with doctors. Please do not get me wrong, my doctors were excellent with their areas of expertise and know-how, but their bedside manners weren’t always the best. I attributed that lack of feeling to the reality of time constraints, pressure of taking on too many patients and so I always “accepted” things. I told myself that I was “asking too many questions” or “being too emotional” when in reality I knew my feelings were rational and valid. I wanted more time, more sensitivity, more than just getting the medical facts and putting a plan into action – I wanted the “feeling” part of it! From that pivotal moment in the interview, I knew that I was about to connect in a way that I never thought possible with an interviewee.

Dr. Wang thanked me for sharing my story with him and continued to reference his own experiences.

DMW: As a doctor, I have to constantly remind myself that my most important duty is to make a patient happy. To do that, I have to start by listening to my patients, to put myself in their shoes, to understand how they feel, and do my best to not only treat the medical conditions, but also and even more importantly, to make them happy. To truly make my patients happy, I need to build an emotional connection with my patients, and that is what often is missing in today’s medicine.

In comparing practicing medicine with dancing, there are many parallels. Being involved with the dancing helped me tremendously with my practice of medicine. When I was younger, at Harvard we had a special teacher come in to educate students about dance. The teacher explained that the most important fundamental of ballroom dance is to be sensitive to and be aware of not only the physical position of your partner, but also the emotional position, and recognize that in order to dance well together, one has to communicate and connect with one’s partner. Before a man leads, there is an essential part called “pre-lead”, in which the man does not move yet, merely expands within oneself and indicates to the lady his intention of moving. Then, he needs to give her the time to express her feeling and intent. Then, the two partners need to communicate, compromise, and ultimately come up with a unified plan, not his original plan, not hers, but theirs. And then, only then, when they both understand the timing, the musicality, the rhythm and amplitude, do they begin to move together. So, ballroom dancing is more than music, more than exercise, it is about human connection, about sensitivity and awareness of another human being, about being willing to adjust, compromise and find a common ground.

With this example, I recalled my dance lessons at the Fred Astaire Dance Studio in Wellington, where my instructor Michael Chaves was showing me the tango (one of my favorite dances). He had used the “Preleading” technique with me. Michael said, “When you feel me pull one way, it is a signal for you to pull forward or back and move in a new direction.” So, when I danced, I focused; I worked as a team with my partner. Subsequently, when I felt happy, my dance moves were smoother. In the same respect when I was nervous or anxious, Michael could “feel” this anxiety through my movement and expression.

Dr. Wang continued gracefully.

DMW: When I practice medicine, I treat it like a dance. When dancing with a partner, sometimes you have to “compromise” movements with your partner. Maybe you need to go one way and she needs to go a different way and the actual direction that you began with ends up being a whole new direction for the both of you. In comparison with medicine, the patient and the doctor are like the dancing partners – they are on a journey of togetherness and they cannot do either alone. The relationship is of a symbiotic nature and just like the dancers, each “partner” must feel what the other is feeling, and so gain better perspective and understanding of each other. Although there is no “music” in medicine, the patient and the doctor must also be in synch with timing, rhythm, and progress of communication and medical treatments. The doctors need to be not only aware of the medical condition of our patients, but also, and even more importantly, the emotion and feelings of our patients. Taking care of a patient to me is like a dance, it “takes two to tango”.

When I talk with a patient, I treat him/her like he/she is the ONLY patient in the world. I know in my heart that my patients are in the best position to describe how they are seeing, since they are the only ones, not us the doctors, who are seeing out of the eyes that we are trying to treat. Doctors today tend to override patients’ feelings. Like in dance, you have to “feel the response” of our patients when we prescribe treatment, sense their emotions and make sure that they do understand and have the opportunity ask any question that they may have. A medical treatment is a journey that deals with not just symptoms and treatment, but also a patient’s emotion and feeling. The “music” guides the movements of medical conversation, and the partners act as a cohesive team in both the music/dancer relationship and the patient/doctor relationship. Just like in dance, partners have to truly understand each other. At the end of the day it is a “journey”- a joined journey between the doctor and patient. It is about what the patient understands that is most important. Without that feedback, doctors cannot do their jobs properly. From dancing, I have learned sensitivity, awareness and the ability to feel what my patients feel, which helped make me a better doctor.

I complimented Dr. Wang on his very compassionate methodology for taking care of his patients. I told him that he should “train other doctors”. He laughed and said, “Actually I have done that too!” He commented on how he has been giving a lecture called “A Doctor’s Duty” to young doctors from around the world. He has three slides.

DMW: I put up the first one first, which says: “Making money”. Then I ask, “Is there a more important duty for you as a doctor?” Usually some students raise their hands and say, “To treat a disease”. I then put up the second slide “Treating a disease”.

But then I ask my next question: “Is there a more important duty for you as a doctor than treating a disease?”

Usually, the entire audience of young doctors get stumped.

I then tell them a story. Mr. Smith is a patient of Dr. Johnson who is a hypertension specialist. Mr. Smith showed up at the door of Dr. Johnson one day. Without giving Mr. Smith a chance to speak, Dr. Johnson went ahead and instructed a nurse to bring Mr. Smith in and checked his blood pressure, which was indeed high. Dr. Johnson gave a refill med prescription and waved bye bye to Mr. Smith. But Mr. Smith just sat there, not leaving, unhappy, and said: “Dr. Johnson, that is not what I am here for”. Dr. Johnson replied, “I know what you are here for. You have been my hypertension patient for 20 years, and I saw you earlier today at the door, and I knew why you were here, since you missed the last visit and refill of meds, your blood pressure would be high. And am I right? I know what you need and I have already taken care of that for you, bye-bye”. But Mr. Smith was still unhappy, sitting there, mumbling, “But Dr. Johnson, that is not what I am here for”. Seeing Mr. Smith just wouldn’t leave, Dr. Johnson finally reluctantly pulled up a chair, and sat down in front of Mr. Smith, and said: “OK, then tell me what you are here for Mr. Smith”. Mr. Smith replied, “Dr. Johnson, I am not here for hypertension, I am here because I broke my leg last night”.

With this punch line, I put up my third and last slide, about “a doctor’s duty,” and that slide says “To make a human being happy”. “That”, I conclude, “is the most important duty for us as doctors.”

Then I ask the young doctors: Can you make someone happy . . .

- Without listening to them?

- By not understanding and feeling their pain and suffering?

- By not understanding that taking care of a patient is ultimately a two persons’ joint journey?

The best doctor is someone who not only is good with his/her medical skills, but also and more importantly, is a good listener and is emotionally connected with his/her patient, understanding the ultimate goal of medicine is to make someone happy.

AW: In your book, From Darkness to Sight, you highlighted your experience of being “fascinated” with America, and how you wanted to feel the freedom and the sense of “belonging”. Looking back now, what advice would you have given to your “younger self” when you were struggling to make your “American Dream” come to fruition?

DMW: I would offer two pieces of advice. I would tell my younger self that America is indeed the GREATEST country on this planet because it has the freedom and the opportunity that is lacking in many other countries. Secondly, I would say that external factors such as having the freedom is 40%, less than half, of the equation. Yes, we need it, but there is more to it than that; The majority (60%) of our success comes from us internally, from our inner determination and drive. Without a good environment such as living in a great country like America, yes, it is indeed hard to succeed, but even if one does live in a free country like America, if one does not have the internal drive, determination and motivation, one still won’t be successful. So, young man, yes, try to find the best place, the freest country to live, yes, that gives you the freedom and opportunity. But what I have learned in the last 35 years is that true success is ultimately determined by if one has the inner drive and motivation. With motivation, one may be successful (and more likely so in a great country like America). But without motivation and hard work, one will never be successful no matter where one lives.

No country is perfect, in fact, I have had my share of experiences with racial discrimination in America. At John Hopkins University when I was trying to apply for medical school here in the U.S., I was faced with discrimination. I was also racially discriminated against when I was dating a Caucasian young lady (by her parents).

AW: There is a popular Shakespearean expression that states that “love is blind”. How would you interpret this statement being that you have restored sight in miraculous ways to so many people?

DMW: “Love is blind” shows that love is more of an emotion than a visual perception. If you love someone you can actually ignore and overlook the negatives of that person. So, love can be emotionally “blinding”. Often in the beginning of many romantic relationships, we are looking at love only through a physical attraction. But for a couple who has been married for a long time, the passion that once existed will not be the same as it was in the beginning of the relationship. The couple may now have issues. Maybe the husband snores too much and annoys the wife or the wife does things to upset the husband. These things were there in the beginning also, but the passion and love, the strong emotions, just blinded them, making them not see the defects.

‘I can see you now!’ Brad saw his wife Jackie for the very first time! (2007)

‘I can see you now!’ Brad saw his wife Jackie for the very first time! (2007)

In terms of patients whose sight has been restored, many of them got married after they became blind and had thus never seen their loved one before. They fell in love nonetheless when one spouse was blind. These are truly cases of “love being blind”. I remember one such couple – Brad and Jackie. Brad got injured when he was 39 in a factory and became totally and (it seemed) irreversibly blind. He had undergone many surgeries in many medical centers which all failed. So Brad was declared to be irreversibly blind. He then met Jackie, they fell in love and got married. So Brad had never seen Jackie, ever. Brad was referred to me from a hospital in St. Louis. I performed the world’s first laser artificial cornea implantation on Brad, and he saw his Jackie for the first time. It was truly a miracle. For Brad and Jackie, the added sight, for Brad to see that Jackie is actually a beautiful young lady, only added additional passion and love to their “blind” love. Few of us know someone who comes out of darkness after 13 years, but even fewer of us are actually there at the moment when one comes out of darkness into light. To be there, for that once-in-a-life-time moment for my patients, to experience with them the ultimate joy and happiness, is what I live for, is what drives me to work hard, to research to develop new technologies such as the world’s first amniotic membrane contact lens that we have invented.

AW: If you could return to any specific time in your life and go back and change the circumstance and outcome, what would it be and why?

DMW: If I had to be honest (which I am, he says with a modest laugh), I would like to achieve a better balance of work and family. I have been so single-minded and focused on my work, I have missed out much of family life and joy with people who are closest to me. I have learned that to truly love others, one really has to first and foremost love the people who are closest to one, first.

AW: One of the most touching parts of your books was the story of Maria, a 15-year-old blind orphan from Moldova. There is a whole chapter dedicated to Maria’s journey. I won’t go into too much detail with this story as it is covered in length and with great sensitivity in your book. However, you talked about how this particular experience changed your life. Can you please elaborate?

DMW: When we regain sight that we used to have, it is already so unbelievably exciting and rewarding. Can you imagine having no memory of sight ever, and then being brought out of darkness, to light and seeing yourself, for the very first time? Maria was a blind orphan who lived in an orphanage in a poor country Moldova. Not only she was blind and did not have any memory of seeing, she also had a bad scar on the eyes, so other kids did not like to play with her. So Maria was blind, and also, alone. A missionary couple found the lonely Maria, and our Wang Foundation for sight Restoration helped brought Maria to the U.S.

The sight restoration surgery was very risky and there was a great chance of failure. Maria’s eyes were scarred very badly. The chance for success was very small (smaller than that of getting heads for 10 times in a row when tossing a coin). We prepared everything, including even the best technology such as the amniotic membrane. The surgery was very long, and at one point, I was on the brink of failure and a looming sense of hopelessness had overcome me. I had to stop and calm myself. I prayed. I needed help from a “higher power”. I regathered my mental strength, and with a renewed focus and clarity, I was able to rescue the surgery, “pulling it back from the cliff”. After the surgery, Maria looked into a mirror, and saw herself for the very first time, and she exclaimed: “I am so pretty!”

When I heard Maria say those words (coming out of darkness into light for the very first time), my life had been transformed forever; I understood my purpose and my life had greater meaning.

AW: You are a coveted public figure, motivational speaker, author of several textbooks, creator of eight major inventions and patents. How do you stay so humble?

DMW: It is only because despite what I have done, I feel that I really have only “scratched the surface”.

There is so much to do – just like America, where we are still struggling with major medical illness such as COVID-19, despite of our medical advances. I am humbled by the fact that not only we still have so much work to do, to advance medicine and treat so many diseases that are still killing our patients, but also whatever that I have done, I did not do them alone. It was my teachers, the privilege of being loved so deeply by my parents, and most importantly, it was God who gave me inspiration to know the purpose of my life and what I am going to use the skills that I have learned for, and that is, to help those who need the most help, the blind orphaned children.

AW: Many of your “miracle stories” dealt with patients who could not afford surgery. Please share with us how you are able to bridge these financial gaps and restore sight to patients.

D.M.W: To help a patient, we must have not only an effective medical treatment, but also it has to be affordable. Medical advances are often expensive, and often the patients who need the most help are least able to pay for it.

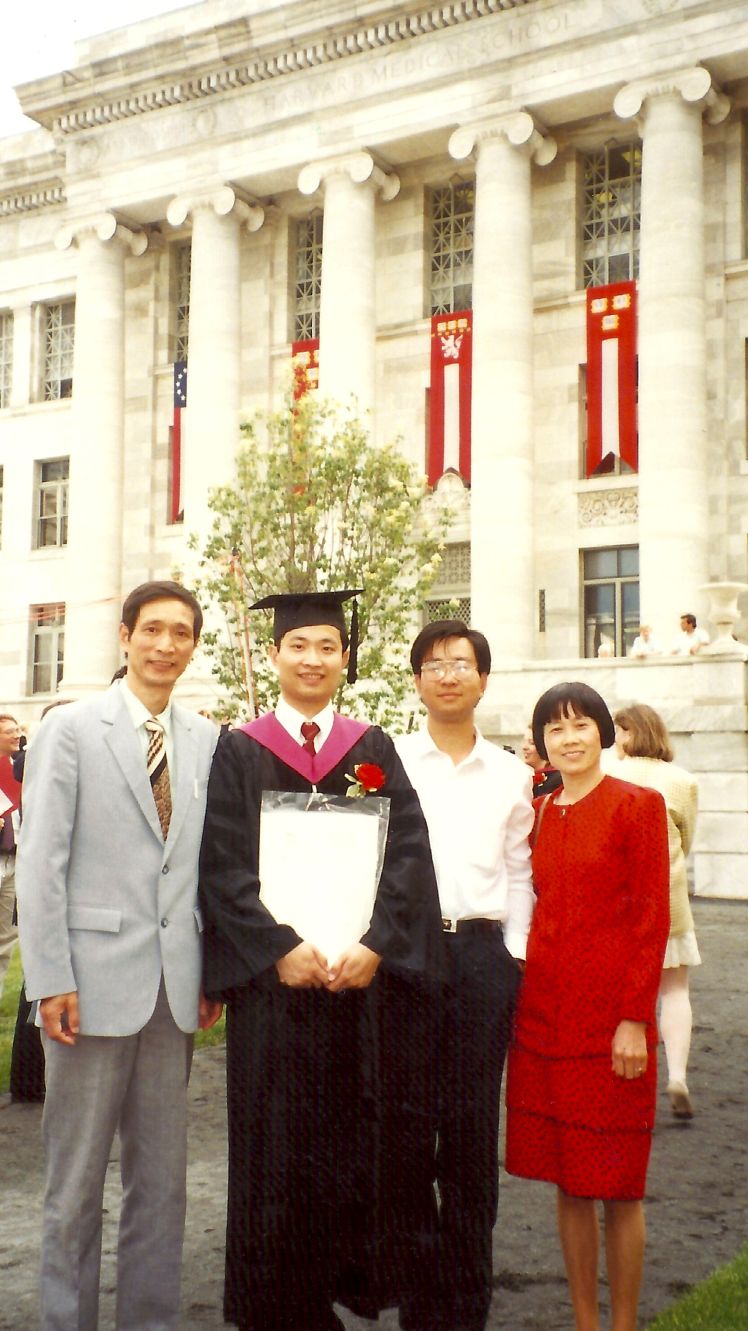

With my parents and brother Ming-yu at graduation from Harvard & MIT (1991) .

With my parents and brother Ming-yu at graduation from Harvard & MIT (1991) .

Hence, I created a non-profit foundation that made it possible for financially disadvantaged patients to have sight restoration surgeries at no cost. I asked many doctors: would you like to help? And many of them say yes. Then I ask, how come you are not helping any patients who could not pay? The answer is that the doctors don’t have the time to leave their offices and to go to an inner-city charity clinic. And also, these charity clinics are often run down, with outdated and not well-kept equipment.

I then devised a creative model: we ask the doctors stay at where they are, i.e., their private clinics. Our foundation triages the patients, to the doctor with the appropriate specialty. As long as the charity patient load is low (less than 5% of the total number of the doctor’s private patients), many doctors are willing to see these charity non-paying patients. Furthermore, since these patients are seen in the doctors’ private clinics, these indigent patients also enjoy the best quality of care with the most updated equipment.

Then, we ran into another problem. In America, patients are suing doctors left and right. The legal healthcare system is totally screwed up in the U.S. To sue a doctor is so easy, that a patient actually does not have to spend a penny! So many foundation doctors that I have recruited were hesitant to see these charity patients, particularly since the doctors get no pay.

Then, we found the solution. There is “good Samaritan” law which says that as long as the care is free, it is legal to ask a charity patient to sign an agreement in which the patient will never sue the doctor who provides free care.

The foundation was thus set up and started helping patients. Today, our 501c(3) non-profit Wang Foundation for Sight Restoration has helped patients from over 40 states in the U.S. and over 55 countries worldwide, with all sight restoration surgeries performed free-of-charge.

AW: You have dealt with oppression and racism many times in your life, especially growing up in China and also in the U.S., being judged by a particular stereotype. Can you share one of the most blatant acts of racism that affected your life? How has it affected your beliefs?

DMW: During that period, all universities and colleges were shut down for 10 years (1966-1976). All high school graduates were sent away to labor camps and were condemned to a lifetime of poverty and hard labor. I decided to play a musical instrument and learn to dance to try to avoid being sent to a labor camp. If I could play the instrument or dance well enough, I could get into the communist song-and-dance troop.

It was illegal for me to study to become a doctor and earn that degree, but I wanted to study medicine so badly. My father was very courageous and “smuggled” me into a medical school run by other professors he knew. I was terrified, for fear of being discovered by the government and then being deported to a labor camp. Also, I had no idea why I should study medicine when the government had given me no chance, whatsoever, to become a doctor. I asked father, why should I study medicine? And he said knowledge is useful, knowledge is always good.

In 1982, I came to America, with $50 in my pocket and a student Visa, knowing no one in this country. I could hardly speak English, but had a big American dream in my heart.

In America, my old dream of becoming a doctor emerged again and I knew that in a free country like America, maybe I would finally be able to realize this dream.

I made an appointment with the Director of Admission at Johns Hopkins Medical School, Dr. Norman Anderson. I was a poor boy with poor clothes from China, but I was willing to work hard to do my best. But Dr. Norman Anderson had already prejudged me. As soon as I had told him I was from China and came to America study, without even looking at my resume, he told me straight, “You are from China, I don’t think you have what it takes to get into an American medical school. It is hard for even American college graduates to do so. I suggest you don’t waste your time here,” and he just walked out!

Dr. Anderson judged me by my skin color and ethnicity, without bothering to look at the content of what I had done or my character.

I thought that I was in a great country now, and everything should be fair now, but not so. Every society has its good and bad people I guess. Thankfully, I did come to understand that Dr. Anderson’s racism was actually not representative of all Americans.

I decided to fight against racial discrimination. Without having a pre-med preparation, my chance of getting into medical school in America was extremely slim. But I persevered, and I wanted to do my best, to not only try to get into medical school, but also to show people like Dr. Anderson that racial discrimination is wrong!

I found out that if I could enroll in the Stanley Kaplan Test Center that could give me the only (but still very slim) chance to get into a medical school in America. However, I needed $1500 to pay for the Kaplan Center studies. So, in addition to working full time for a doctorate degree in laser physics, I took on 3 more part-time jobs: weekday evenings working at Burger King and helping a professor clean their house, and weekends at a Best Western Hotel.

I scored nearly perfect in most of the subjects in MCAT (Medical College Admission Test) and got into both Harvard and Johns Hopkins. One day, I got a call, and it was from Dr. Anderson, asking me why I had not said yes to Hopkins admission letter. I realized that he had no clue that I was the same Chinese student who sat in front of him in his office a few months ago, who he so readily discriminated against, purely because of my skin color and ethnicity. Partly due to Dr. Anderson, I chose to attend Harvard.

AW: “Black Lives Matter” has been the global slogan and principle behind all of the recent protests and rallies bringing awareness to the recent killing of George Floyd and the racism that has spread “like a virus”. What is your advice for a very fragile America, having also been a victim or racial discrimination?

DMW: (in a straight forward, sensitive tone) I feel that there are two important issues here.

First, the tragedy is a powerful example that shows that black Americans are still being discriminated against. It has been 50 years since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. made his “I have a dream” speech, and yet there is still so much racial discrimination, despite of the progress that has been made.

Second, I believe that the only way to improve race relationships is to find common ground. Everybody recognizes the importance of finding common ground, the real question is how.

I have co-founded another 501c(3) non-profit the Common Ground Network, to identify, formulate and teach a set of universally applicable methodologies proven to be effective in finding common ground.

Our nation is polarized. We are often incapable of overcoming our differences in order to find common ground. Our social climate is toxic. The merit of an issue is often not considered as important as power alliances—political, ideological or otherwise. The ever-present media has us glued to our TV sets, watching 30-second dramatic images that short-circuit our imagination and independent judgement, and polarize us. Civil discourse and debates that are focused on the issues themselves–without insulting the opponent–have become rarities. We have departed from the principles of free speech and mutual respect and have instead replaced them with intolerance and intimidation. We are becoming a society that is increasingly fixated on our differences, rather than appreciating what we have in common.

The ability to find common ground in a polarized world is only achieved through years of learning and practice. We must first learn to listen, so that instead of trying to score rhetorical points through well-rehearsed sound bites, we may learn valuable information—even from our opponents—that may propel both sides toward breaking the gridlock which is the hallmark of our current national discourse. Solutions to difficult problems will come only through collaboration, not alienation. So that not only are we ready to deal with a crisis like this, but also to able to solve our society’s problems in general.

AW: I understand that your life is going to come to the “big screen”. Please tell us more about this exciting opportunity.

DMW: Yes, this is true! My autobiography “From Darkness to Sight” is being made into a major motion picture right now. We hope to start casting in the summer and shooting in the winter of 2020. The movie is called “Sight”. It will be predominantly in English, but the parts that depict the political happenings in China will be in Chinese with English subtitles. I am excited about the movie! The movie will span across a tremendous range of human experiences.

– in time (from 1966 to today)

– in space (from around the globe, from China to America)

– in cultures (from the East to the West)

– in epic human events (from the 1960s’ China to the 21st century’s conflict between science and morals/ethics)

– in societies (from Communism to a free, capitalistic society)

– in languages (from Chinese to English)

– in beliefs (from an atheist to a person who is now inspired to believe)

Note: The actor who plays me is better looking than me (he laughs).

AW: I hope that one day you have the honor of meeting Dr. Ming Wang. Although he is famous for his phenomenal work with laser surgery, he has also brought “vision” in so many other ways. In the short time that I have known him, I have surmised that he will be a soul connection in my life- a mentor, a voice of reason, and example of humility and not your typical “achieving the American Dream” prototype. Dr. Ming Wang may be a name that you didn’t know before this interview, but now it is one you will never forget. Read, explore, open your minds and of course . . . READ THE BOOK!

Author Denise Marsh upon first meeting Dr. Ming Wang at the Goldcoast Ballroom in Coconut Creek, FL on February 29, 2020

Author Denise Marsh upon first meeting Dr. Ming Wang at the Goldcoast Ballroom in Coconut Creek, FL on February 29, 2020

Dr. Ming Wang is a Harvard and MIT graduate (MD, magna cum laude) and one of the few Cataract and LASIK surgeons in the world today who holds a doctorate degree in laser physics.

Dr. Wang founded a 501c(3) non-profit charity, the Wang Foundation for Sight Restoration, which to date has helped patients from over 40 states in the U.S. and 55 countries, with all sight restoration surgeries performed free-of-charge. He was named the Kiwanis Nashvillian of the Year for his lifetime dedication to helping blind orphan children from around the world.

Dr. Wang is the co-founder and president of the Tennessee Immigrant and Minority Business Group, and the co-founder of the Common Ground Network, a 501c(3) non-profit organization that focuses on Dr. Wang’s lifelong mission to help people find common ground and solutions to our society’s problems.

From Darkness to Sight, Dr. Wang’s autobiography has inspired the upcoming movie Sight.

Dr. Ming Wang, MD, PhD – can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..