By Joe Bendel, May 22, 2024, Cinemadailyus.com

China’s Cultural Revolution is having a pop-culture moment. In Netflix’s Three-Body Problem adaptation, the cruelty of the extreme Marxist movement causes a central character to literally turn against the human species. Dr. Ming Wang also witnessed the student revolutionaries’ brutality as a child during the 1970s, but in this film, he responds by embracing humanity and public service instead. Eventually, Dr. Wang became one of the world’s leading eye surgeons, but failure tests his spirit because it means disappointing his patients. Dr. Wang is particularly determined to cure a little girl who reminds him of his past in Andrew Hyatt’s Sight, which opens Friday in theaters.

Viewers know Dr. Wang’s story will be inspirational, because it comes from Angel Studios, the distributors of the Biblical series, The Chosen, and the controversial The Sound of Freedom. However, nobody mentions Jesus or an Abrahamic God in this film, proper. Of course, anyone overheard discussing Christianity during Wang’s childhood amid the Cultural Revolution would have been beaten and likely murdered. It was a chaotic time when cadres of Red Guards terrorized society, attacking old Chinese culture and anything considered Western, including fields of higher learning. Technically, they operated outside official government channels, but their reign of terror helped Mao re-assert his hold on absolute power.

At the time, the politics were all beyond young Wang’s understanding. He just wanted to study hard, so he could become a doctor like his father. Unfortunately, teenaged Wang’s dreams are temporarily dashed when the Red Guards close his high school. Pivoting, his father teaches him to play the erhu (a traditional stringed instrument, played with a bow), hoping Wang can scrape out some kind of life under the radar as a professional musician. Wang maintains a love-hate relationship with his instrument, but his friend Lili and her blind father always enjoyed his playing.

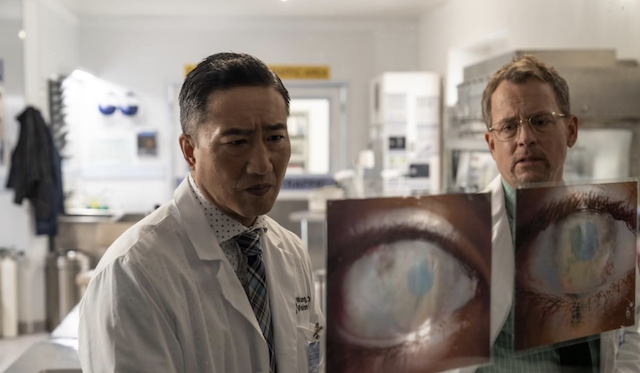

Years later, it remains painful for Dr. Wang to remember their fates. As soon as he meets Kajal, an incredibly fragile-looking Indian orphan, he is determined to help her. He refuses to admit it to his colleague, Dr. Misha Bartnovsky, but something about Kajal reawakens all his anguished memories of Lili. Sadly, the young girl now in the protective care of Sister Marie, will be a particular tough case.

Evidently, her wicked stepmother deliberately blinded Kajal with acid, so she would be more successful as a street beggar. According to “Sight,’ this is a brutal, but not so uncommon practice. Frustratingly, the damage done cannot be treated by conventional methods—at least not at the time of Kajal’s consultation. Dr. Wang will devise an experimental treatment, but the term “experimental” clearly implies a real chance of failure.

The inspirational implications of Sight are undeniable, but it realistically refrains from tying up every narrative strand in a compulsively happy bow. Dr. Wang will not be able to cure every patient. He is a doctor, not a miracle worker. Despite the film’s Evangelical leanings, Hyatt’s screenplay, co-written with John Duigan and Buzz McLaughlin also decries the racism Dr. Wang endured during his early years in America, as a med student.

Compared to Three-Body Problem, Sight depicts the Cultural Revolution with less brutality, which makes sense, considering it was produced with family audiences in mind. Nevertheless, it is readily apparent how the kind of violence young Wang witnesses, but is powerless to stop, would be deeply traumatizing.

Fans who recognize Terry Chen from his supporting work on shows like Jessica Jones, The Expanse, and the Kung Fu reboot should be happy to see him get a significant leading role. Chen is convincingly intense as the cerebral adult Wang, but he depicts the emotionally reserved doctor’s processing of past trauma with understated grace. It is a quiet performance, but it resonates.

Throughout Sight, it is easy to differentiate the timelines, because the teen Wang is portrayed by Ben Wang (the next Karate Kid), whose youthful features allow him to credibly play the lead character from 14 to 21 years of age. There is an earnest naivete to his performance that contrasts dramatically with the horrors of the Cultural Revolution and the casual indignities of Western racism.

Dr. Bartnovsky is a classic sidekick role, but Greg Kinnear portrays him with great warmth and sensitivity. If he ever leaves Hollywood for medical school, Kinnear’s bedside manner should be calmly reassuring for prospective patients. He and Chen have a nice rapport together, so it is easy to understand patients entrusting their eyes to their respective characters.

The misfortunate Kajal functions more as a symbol than a full-fledged character, but young thesp Mia SwamiNathan shows exceptional poise. Raymond Ma adds quiet poignancy as Wang’s elderly father, Dr. Zhensheng Wang (he is a survivor, but not without scars of his own). Plus, Garland Chang nicely provides the film’s only comic relief (which is definitely appreciated, given the heavy themes), as Wang’s slacker brother Yu.

This is a heartfelt film, but it is never simplistic. Hyatt and company strive to inspire, but the film recognizes life is never perfect. It is not preachy either, at least until the real-life Dr. Wang directly addresses his faith for the audience’s benefit in an afterword, right before the closing credits roll. Of course, anyone who does not want to hear his testimony can safely leave at that point—just respect those who want to hear the message.

After all, Wang’s story and his commitment to public service are quite laudable. Hyatt and his cast present his story in an accessible manner, with the benefit of a classily crafted package. That notably includes Sean Philip Johnson’s score, which elegantly integrates the styles and instrumentation of Western and Chinese classical music. Highly recommended for fans of medical and historical dramas (as well as the built-in Angel Studios market), Sight opens Friday (5/24) in theaters.

Grade: A-